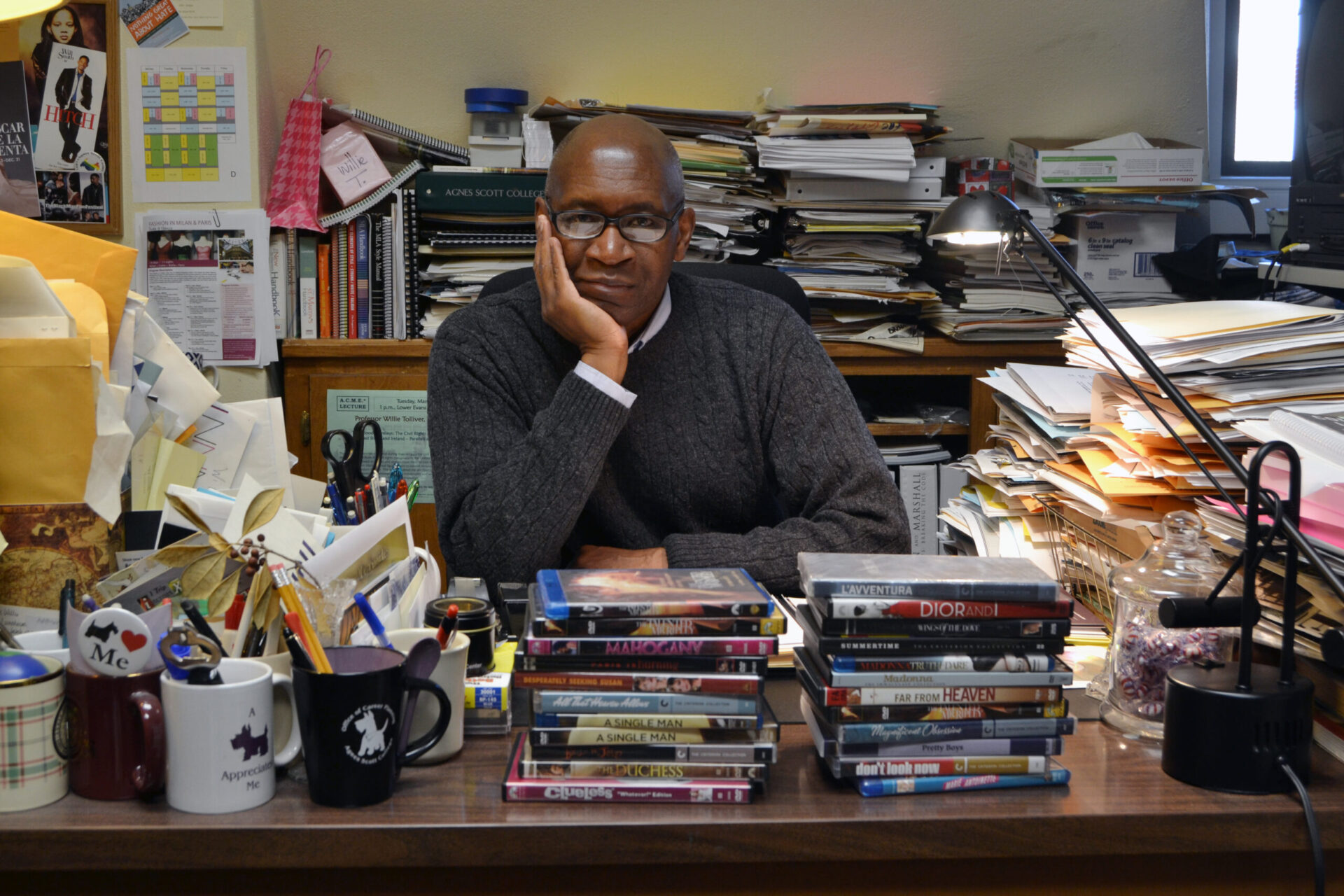

showing/thinking: Yvonne Newsome

Yvonne Newsome is a professor of sociology at Agnes Scott College. She holds a B.A. and M.A. from the University of Memphis and a Ph.D. from Northwestern University. Professor Newsome’s research interests center on racial-ethnic identity and relations; race, class, and gender intersections and inequality; social problems; sociology of education; comparative historical methods political sociology; qualitative sociology; and transnationalism. She teaches courses in African American culture and social institutions; African American images in popular culture; marriage and the family; schools and society; and the senior research seminar. Below are Professor Newsome’s reflections on her scholarly thinking and process, from the 2018 Dalton Gallery exhibition showing|thinking, a series of exhibitions that highlighted the work of faculty and staff on campus:

“There is no such thing as a single-issue struggle because we do not live single-issue lives.” -Audre Lorde

“Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere.” -Martin Luther King, Jr.

At first glance, my scholarship and teaching interests may appear to be overly broad, and haphazard; however, they are stitched together by a common thread, which is my abiding concern for and commitment to social and economic justice. My lifelong goal is to devote my expertise to deconstructing, unveiling, and dismantling the matrix-like domination system that both incorporates and circulates through and across race, class, gender, and sexuality. To achieve these ends, my scholarship applies critical theories, social constructionism, and black feminism, each of which facilitates my drive to understand and explain how dominant groups wield their collective power to maintain their privileges as well as how subordinated groups mobilize to resist and transform oppressive ideologies, policies, and practices. My preferred research methods vary and depend upon the questions that I am exploring; however, most of my research studies are qualitative and involve the use of questionnaires, archived documents, interviews, ethnography, and discourse and visual analysis.

My passion for social and economic justice stems from my personal biography as well as from the historical experiences, collective memories, and undying agency of African Americans as a people. I am a Southern-reared, working-class origin, African American woman sociologist of the late twentieth and twenty-first centuries; however, my individual life has been greatly influenced by the enduring, legacy of oppression and resistance that has characterized African American women’s lives, intellectual work, and activism down through the generations. I am a black feminist. This means that I not only embrace the theoretical standpoint that various kinds of domination systems interlock, but also that these systems operate simultaneously (rather than singly) to mete out different kinds and amounts of privilege and oppression to people who are differently positioned at the intersections of the race, class, gender, and sexual hierarchies. Because of this structural and ideological convergence, I hold that no domination system can be substantially dismantled so long as any other domination system goes unchallenged and remains standing.

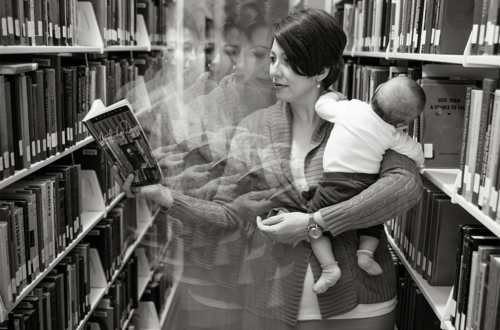

Two additional guiding principles for my work have cultural and social scientific foundations. First, my African heritage teaches me that one achieves nothing alone and, moreover, that we who are extant stand upon the shoulders of those who preceded us. These beliefs are expressed by the Akan concept of Sankofa, which advises the living to bear no shame in reaching back to the forgotten past to learn from it and move forward. Second, “the sociological imagination” cautions that “No social study that does not come back to the problems of biography, of history and of their intersections within society has completed its intellectual journey” (Mills 1959: 6). In other words, far from being disparate phenomena, history, personal biography, and social relations link together individuals, institutions, societies, and events across time, place, and social locations.

Indeed, my own personal biography, group- affiliated identities and histories, and contemporary conditions swirl in a complex mixture that yields a rich and deep font from which to draw topics for investigating and teaching about inequality and justice. For example, my first awareness that racism is institutionalized resulted from a personal experience that occurred at age eight. The third-grade classes at my racially segregated, public school had received “new” textbooks from a local, all-white school. Our “new” books were tattered, written in, and more than ten years old. It suddenly occurred to me that we had received the white school’s throwaways. This was a critical turning point in my intellectual development. A light switched on, and an alarm went off. Racism was something much deeper and more complicated than prejudiced “extremists” who refused to change with the times. Racism was built into the very structure of institutions, and it was being justified by contradictory propositions (like “meritocracy,” “democracy,” and “the land of opportunity”) that were neither supported by the facts of my biography nor by those of my immediate family, kin, community, and ethnic group. Out of the embers of that soul-crushing realization, a sociologist was spawned. I had yet to acquire the vocabulary to describe what I was observing and becoming, but from that day forward I was determined to find answers to the perplexing questions that my enlightened consciousness raised.

A second incident, which occurred just three years later, instilled in me the obligation to play an active part in fighting to end oppression. Like most children, I had always admired and appreciated my parents. I was acutely aware of their many struggles to feed, house, clothe, educate, and encourage their children to excel and live honorably in a society that placed imposing barriers in their paths. My appreciation deepened into awe when, on the ominous evening preceding Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.’s assassination, I learned that fear of harm or loss does not excuse one from standing up for what is just. It was the night of April 3, 1968. Striking Memphis sanitation workers held a protest march, and my father, a self-employed landscaper who contracted with Memphis-area builders, chose to support the protesters with his participation. Curious child that I was, I trailed my father into my parents’ bedroom and espied him secreting away a placard into their closet. Both parents appeared alarmed and discomforted by the fact that I had seen the placard. Its message, now deeply engraved in my memory, stated in bold, capitalized black letters: “I AM A MAN.” Raising a finger to her lips, my mother “shushed” me and admonished me not tell anyone what I had seen because “Daddy could lose work.” For African Americans in the South, those were perilous times. I knew (and had seen on television) that white authorities routinely assaulted, jailed, and even killed rebellious black people who dared to demand recognition of their civil and human rights. I immediately ascertained that my father’s activism risked his own and his family’s physical and financial security, but the message to me was emphatically clear. No matter what the potential consequences, every ethical, freedom-loving individual must stand up for justice. I likewise learned that courage does not negate fear. Choosing to confront and override one’s fears is courage, and the times had demanded that my parents demonstrate it.

As I matured, my comprehension of and concern over social inequality became increasingly sophisticated and ingrained. A lifetime of day-to-day encounters with microaggressive behaviors, overt expressions of bigotry, and both subtle and manifest systemic impediments steered the trajectory of my career choice, training, research agenda, pedagogy, service, and activism. Sociology—with its scientific examination of society, social relations, institutions, and belief systems—was the conduit through which I acquired the analytic and explanatory frameworks, methodological tools, and sheer inspiration to embrace and pursue the calling of scholar- activism. To date, my work has explored how systems of domination interlock to affect the distribution of resources and power, social positions, identities, intergroup relations, ideologies, politics, popular culture, discourse, social problems, institutional access, and social movements. Examples include investigations into the causes of the sharp decline in African American women’s earnings during the 1980s; the effects of Jewish and African Americans’ transnational identification with their respective “homelands”–i.e., Israel and the African continent–on their intergroup relations in the United States; and the disproportionate targeting and intersectional profiling of African American women travelers who cross the U.S. border. More recently, I have examined President Barack Obama’s social justice agenda; the political discourse of the anti-Obama “Birther” movement; stereotypic representations of black motherhood in award-winning Hollywood movies; and a comparison of the recurring filmic associations of fictional black presidents with incompetence, idiocy, savagery, catastrophe, and the end times with disturbingly similar, real-life media and political representations of Barack Obama.

I sincerely hope that my scholarship and teaching have value to those who share Dr. King’s vision of the “Beloved Community.” In the meantime, I will persist with my efforts to broaden knowledge of how social structure, unequal power relations, system-supportive ideologies, and day-to-day processes operate to generate, uphold, and reproduce the matrix of domination and subordination. At the same time, I will strive to unearth and suggest effective strategies for deconstructing, subverting, and transforming the same. No doubt, the intersections of history, my own biography, and ongoing developments will continue to inspire my work.