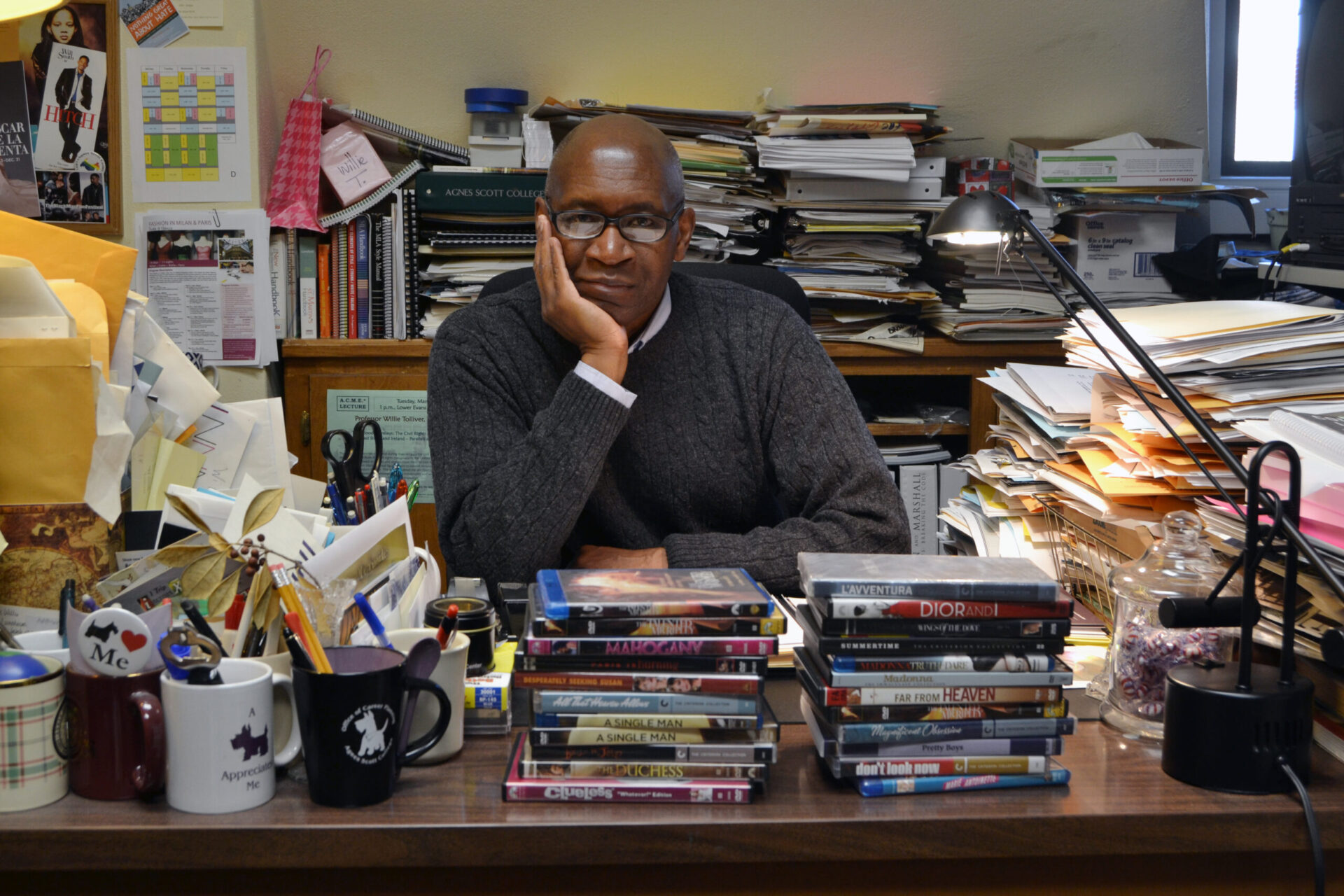

showing/thinking: Willie Tolliver

Willie Tolliver Jr. is a professor of English at Agnes Scott College. He holds a B.A. from Williams College and an M.A. and Ph.D. from the University of Chicago. Professor Tolliver’s interests include African-American literature, nineteenth-century American literature, Henry James, and film. Below are Professor Tolliver’s reflections on his scholarly thinking and process, from the 2018 Dalton Gallery exhibition showing|thinking, a series of exhibitions that highlighted the work of faculty and staff on campus:

I started to go to the movies seriously as a precocious schoolchild in the 1960s. After viewing such films as Antonioni’s Blowup or Tony Richardson’s The Loved One at the Uptown Theatre in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, I would come home and write down as much as I could about the films: the plot, the dialogue, the characters, the setting, the costumes, the camera movements. It was an attempt to hold on to the memory of the magic experienced in the dark. This was the beginning of a connection between writing and the visual that informs my teaching and research today.

Many of the ideas that animate my work have had their source in an image. I can even trace the inception of my sense of vocation as a writer and scholar to an image: the portrait of Henry James by John Singer Sargent that appears on the cover of Leon Edel’s five-volume biography of the master. Reading each volume during summer vacations from college, I was intrigued by how that observant and reserved adolescent became one of the greatest figures in American literature. There was a moment in his young life that resonated for me. During one of his first visits to the Louvre, in the Galerie d’Apollon, he had an inchoate sense of the world opening up, of possibility, and of the life of literature and art that awaited him. Despite the differences in history, class, and race that separated us, I wanted this kind of life as well. People often ask me why I, as an African American, wrote my dissertation on James, as if his world and work would have little relevance to mine. I have discovered that James has served as an inspiration for and an object of fascination to many black writers, such as James Baldwin and Nella Larsen, and that James himself learned from such writers as James Weldon Johnson. I have devoted a good deal of critical attention to tracing those influences. Making connections between seemingly disparate ideas is essential to the way that I seek out my subjects and pursue them.

In the summer of 1990 I noticed an ad in the New York Times for the premiere of John Guare’s new play, Six Degrees of Separation. It was a poster by the renowned graphic artist, James McMullen, depicting the actor James McDaniel who was starring as the dreaming con-artist who impersonates the son of Sidney Poitier to enter the lives of a series of families on Fifth Avenue. The seated figure, dressed in black tie, is an assured and keen young black man who defies popular stereotypes. My fascination with “Paul Poitier” led me to multiple performances of the play in New York and eventually to the 1993 film version starring the rap and television star Will Smith. As his career took off, Smith ascended to an unprecedented stardom with stunning box-office appeal and global reach. I conceived a research project focused on the analysis of the Smith phenomenon that seemed to transcend race. Why Will Smith? In search of an explanation, I draw upon the tools of my profession, a range of literary theories and perspectives, critical approaches, interpretive strategies, and ways of seeing and knowing. To be more specific, I enlist the insights derived from semiotics, deconstruction, African American film history, black cultural criticism, postcolonial criticism, masculinity studies, the techniques of film and visual analysis as well as theories of celebrity, stardom, and fashion. This is all to frame, contextualize, and substantiate my initial observations and intuitions.

Sometimes my line of inquiry moves forward, leaps forward, by means of epiphanic encounters with images. During my research, I happened upon a small critical book entitled On Black Men by David Marriott, then a professor of English at the University of London. His major claim is that the most powerful images of black men are centered in two of the most complicated and fraught themes in modern art: lynching and pornography. Accompanying his text are transfixing images: the racist photographic nudes of Robert Mapplethorpe and documentary photographs of lynching. This discovery transformed my research. I saw the necessity of reading moments of Smith’s films against these images. The result was a deepening of my project allowing me to make larger claims and to articulate the ways his prominence does significant work in the reconstruction of the black male image in popular culture.

There is another aspect of the utility of images: how they can represent the self. Looking at images, one often sees oneself. As a black male spectator, I look for images that affirm, inspire, and validate. I have never fully seen myself in film or literature, but this objective remains essential to my journey. Seeking the self makes me sensitive to stereotypes and misrepresentation of black men. It also allows me to discern differences in the way men of color are portrayed in films beyond the parameters of Hollywood and America. This has opened up a new direction of research entailing a widening of my perspective to include films from other traditions in Europe, Asia and Africa. I have explored these postcolonial masculinities in essays about the performances and careers of such French Beur actors as Salim Kechiouche and Sami Bouajila and the ways their films write and do not write men of color into a cinematic national narrative.

My scholarly habits have always been inspired by the world of art. During the 90s there arose a discourse concerning the visual representation of black men. This discourse found its moment in the controversial 1993 show at the Whitney Museum of Art entitled The Black Male. In this exhibit of traditional, conceptual, and avant-garde art, seventy-five black artists, mostly male, posed questions about the way black men are perceived in our society. My personal connection to this enterprise was the artist Kevin Everson whose installation, “Mansfield, Ohio, End Table, 1994” recreated a living room coffee table and family portraits in a typical black working-class home, a background our families share. Glenn Ligon perfectly synthesizes literature and art in his giant paintings of African American literary texts such as Invisible Man by Ralph Ellison, or his autobiographical pieces in the form of runaway slave posters or the title pages of slave narratives. My current discovery, the Senegalese photographer Omar Victor Diop, continues this line of expression through his painterly self-portraits as forgotten African figures in European history and as the writers Elaudah Equiano and Frederick Douglass. These artists are important to me as a writer and scholar because I realize that at some level we are all engaged in the same enterprise.