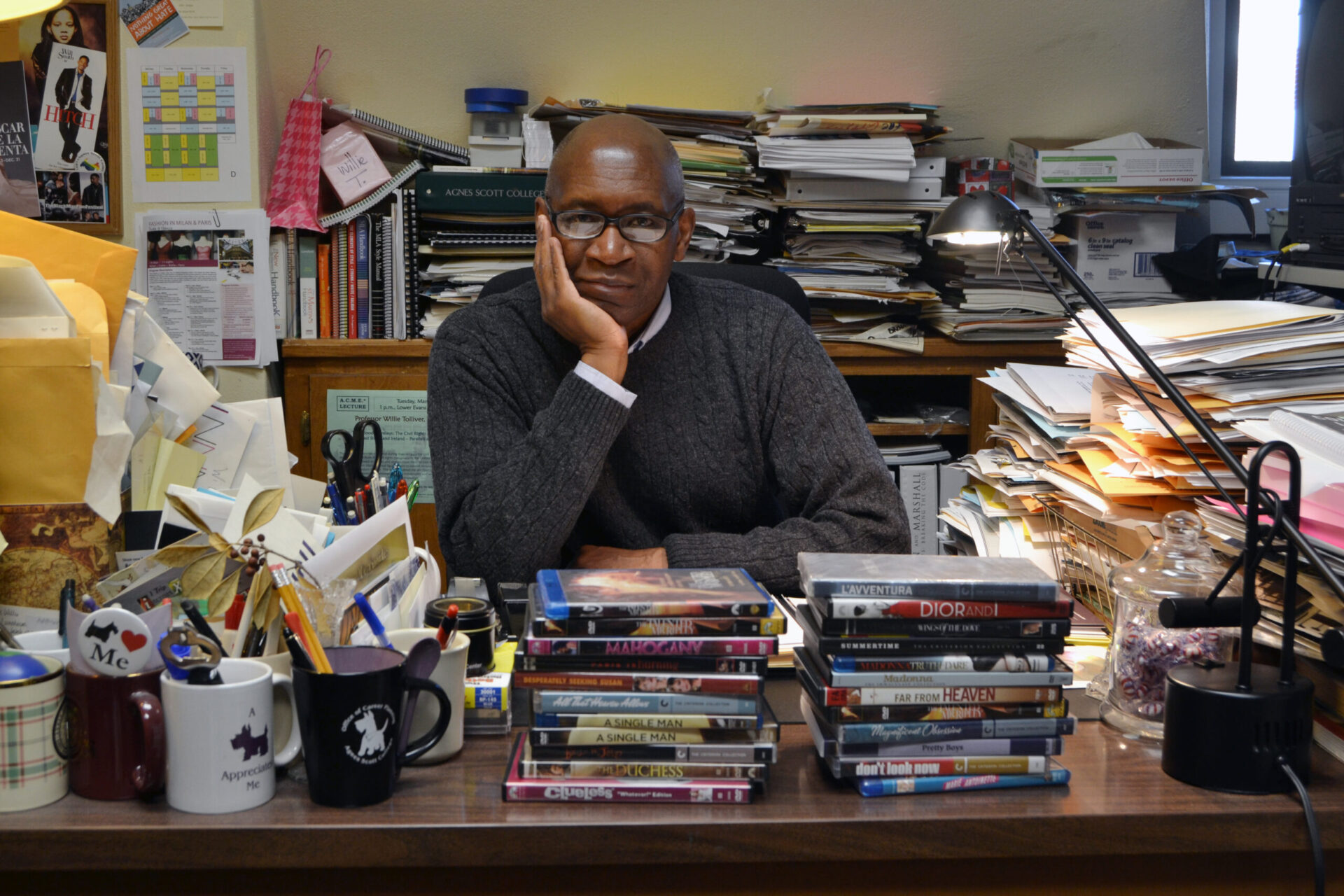

showing/thinking: Rafael Ocasio

Rafael Ocasio is the Charles A. Dana Professor and Chair of Spanish and the Faculty Fellow for the Gay Johnson McDougall Center for Global Diversity and Inclusion at Agnes Scott College. He holds a B.A. from the University of Puerto Rico, an M.A. from Eastern New Mexico University, and a Ph.D. from the University of Kentucky. Ocasio is a literary historian, having published several books on little known figures in Cuban and Puerto Rican history. He also teaches language courses, advanced conversation and grammar, Latin American culture and civilization, and Latin American literature. Below are Professor Ocasio’s reflections on his scholarly thinking and process, from the 2015 Dalton Gallery exhibition showing|thinking, a series of exhibitions that highlighted the work of faculty and staff on campus:

I have always had a strong sense of the importance of history in the development of individuals, families or social groups. I was born of former peasant parents, whose respective families had left the countryside for San Juan in the forties. From them, as a child, I heard countless personal stories pertaining to complex events, many of them related to American- imposed policies that had promoted their families’ displacement from rural living to the booming city of San Juan.

In my critical thinking I tend to compartmentalize cultural items into neatly meaningful categories. I had enjoyed playing the role of a “wanna-be historian,” as an annoying know-it-all teenager who daydreamed about becoming a professor. Growing up in Puerta de Tierra, a working class area, predominantly Black neighborhood in the outskirts of Old San Juan, I often explored my family’s socio-political and economic background that shaped our hybrid traditions.

The role of cultural interpreter can be a tricky one, though, one in which a sense of belonging or allegiance to a group plays an important role. That has been the prism with which I have tackled my role as “cultural informant,” as a Puerto Rican scholar teaching Spanish language and Latin American literatures. My view as a cultural “expert” has evolved as years passed. My initial expertise in “explaining” cultural traditions from a first-hand point of view has now given way to my “re-living” memories of them as a long-time resident of the United States, as a Latino immersed in a more multi-faceted cultural environment than that of my native Old San Juan.

My physical absence from the actual island settings, according to Puerto Ricans on the island, makes me no longer a worthy interpreter of Puerto Rican culture. Indeed, as the Puertorriqueña-Latina Judith Ortiz Cofer reminded me as I read the manuscript of her forth-coming memoir, The Cruel Country, Puerto Rican-born individuals who have lived in the United States for long periods of time become “de afuera,” outsiders to their own native culture. Puerto Ricans experiencing geographically-bound cultural traditions on the island consider Puerto Ricans-de afuera’s critical views of Puerto Rican culture as highly tainted by imprecise memory accounts of their long- gone experiences on the island.

The strong dichotomy of native “de aquí” islanders versus Puerto Ricans-“de afuera” has shaped my exploration of Puerto Rican icons from a variety of socio, cultural and political perspectives. In fact, in hindsight, I also now realize that through all of my life I have viewed the world from the perspective of someone living “de afuera.” The child of former peasants not quite San Juaneros themselves, I was a teenager who attempted to “pass” as a San Juanero, although I was urban by virtue of my experiences in the city, I also lived under the allure of rural traditions. Nowadays, having lived in the United States all of my adult life, not only am I shaped by my memories of those experiences on the island but also by my experiences as a Latino of Puerto Rican background.

I am mindful that I have chosen specific cultural artifacts as examples of a resilient presence of Puerto Rican culture. My own house has become a museum of Puerto Rican cultural icons of all sorts, predominantly of saints, with which I seem to conjure up memories of long time-gone experiences. Currently I am working on a book manuscript that explores the earliest writings by American travelers to Puerto Rico as interpreters of Puerto Rican culture. I have examined numerous travelogues and historical accounts by these “de afuera” American visitors, foreigners to a new culture; they not only attempted to serve as interpreters but also worked out a methodology to phase out Puerto Rican cultural values to be replaced by a mainstream American way of living. One such “de afuera” traveler was the reputable anthropologist Franz Boas, who came to Puerto Rico in 1915 as part of an elaborate scientific- anthropological team of researchers. Boas was among the most notable of “de afuera” American scholars who documented Puerto Rican culture prior to its “predicted” extinction. His trip to Puerto Rico, barely documented both in the United States and in Puerto Rico by his numerous critics and biographers, speaks about the critical biases against “de afuera” researchers.

I intend to challenge the divisive boundaries between island natives, those who proudly label themselves as “de aquí,” and my own “de afuera” views, tainted by other personal experiences foreign to cultural patterns operating today on the island. I intend to illustrate that no one cultural account is more accurate than another. For example, I continue to be surprised by the depth of sophistication that my Agnes Scott College students, most of them Americans from various cultural backgrounds, can achieve in their analyses of Latin American cultural items. It is my objective to bring into a conversation these various critical angles, whether they illustrate the opposite views of those “de aquí” or those “de allá.” These views, like those crisscrossing series of conversations of my childhood and of my years in the Unites States, may be the initial entry to understanding a modern Puerto Rican identity.

Below are images of Ocasio’s gallery installation within the larger exhibition of showing/thinking 2015, which featured four other members of Agnes Scott’s faculty that year. Photo credits: TW Meyer