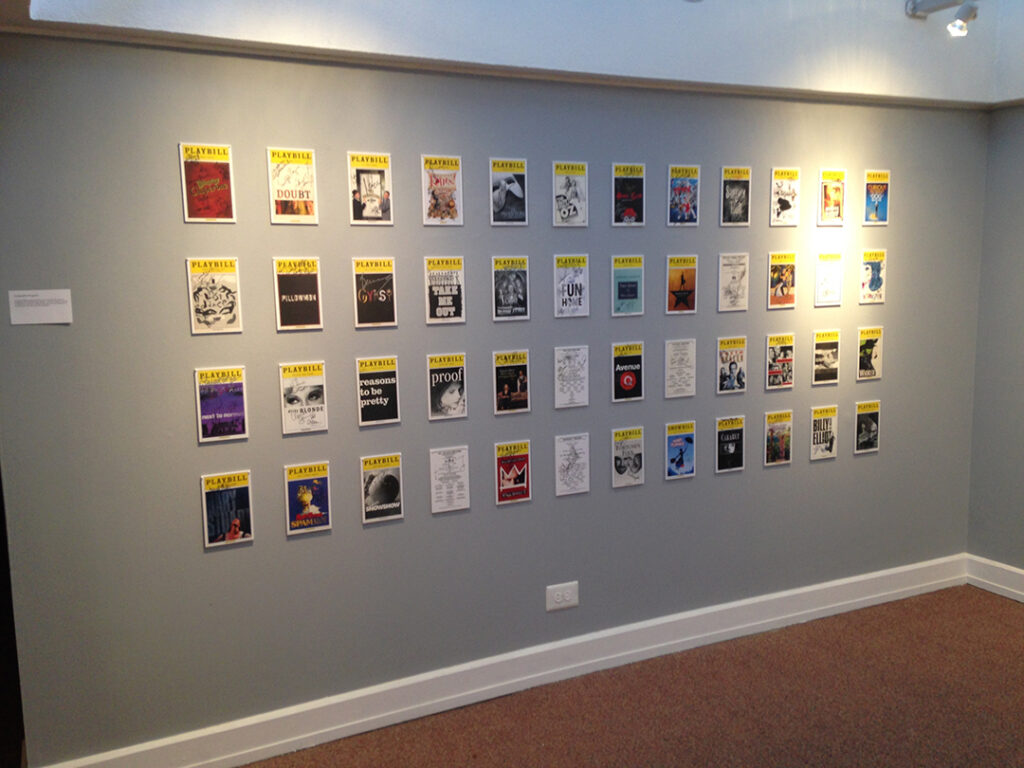

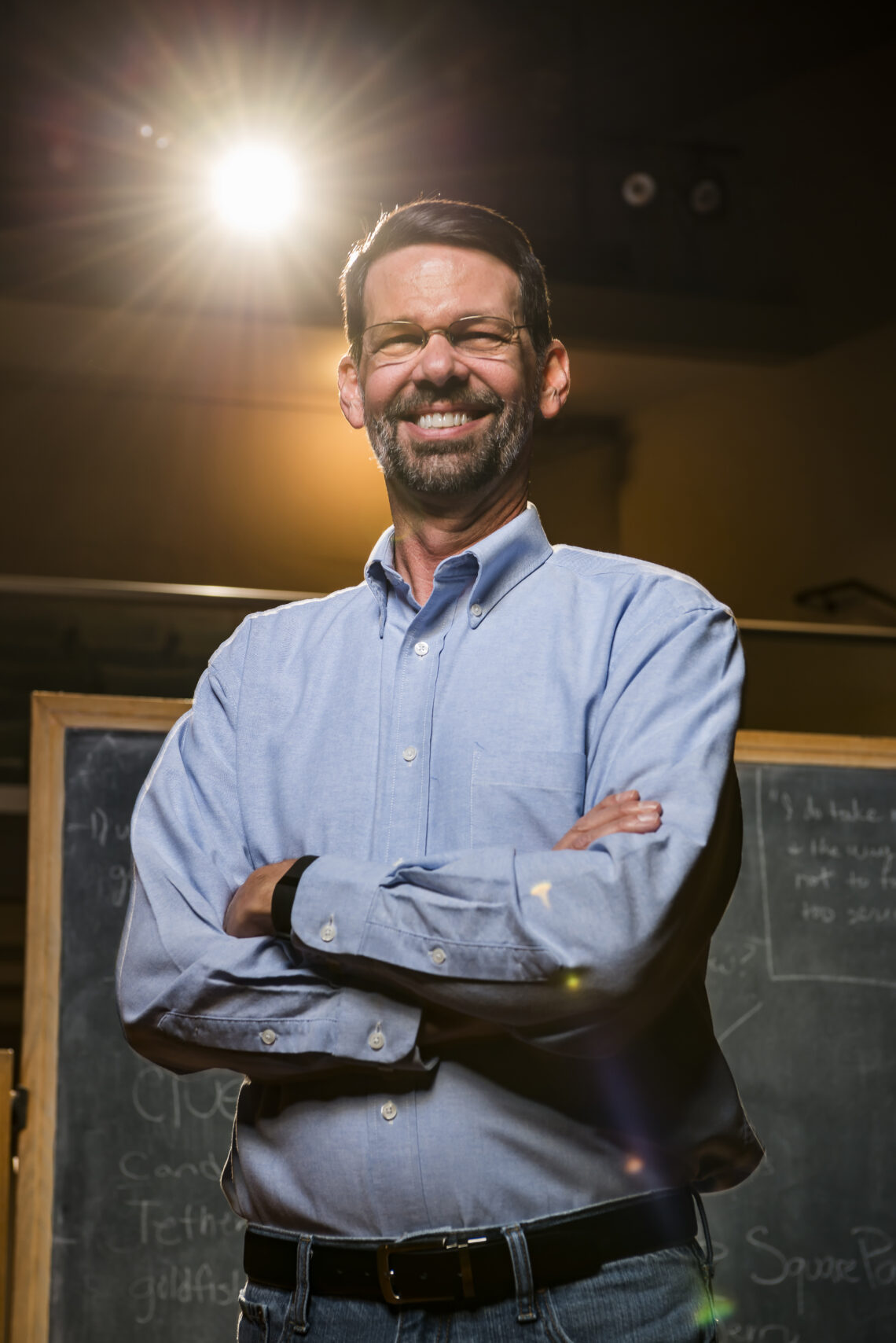

showing/thinking: David Thompson

David Thompson is the Annie Louise Harrison Waterman Professor of Theatre at Agnes Scott College. He holds a B.A. and M.F.A. from the University of Tennessee and a Ph.D. from the University of Texas at Austin. Thompson is an expert on Broadway theatre, particularly the Tony Award, Broadway’s highest honor. He is also an expert on award-winning women playwrights, the topic of his 1997 dissertation. He is a director, theatre theorist, consultant and critic who also researches American drama and the pedagogy of theatre. Below are Professor Thompson’s reflections on his scholarly thinking and process, from the 2015 Dalton Gallery exhibition showing|thinking, a series of exhibitions that highlighted the work of faculty and staff on campus:

“Tremble: your whole life is a rehearsal for the moment you are in now.”

~Judith Malina

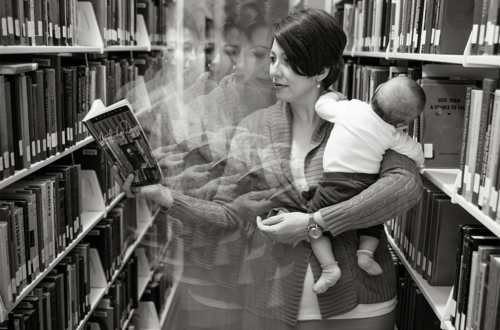

In an era marked by increasing specialization I am proud to call myself a theatre generalist. During my artistic journey, I have seen the sights from the vantage point of an actor, director, and playwright. I have also designed scenery, costumes, and soundscapes, though I doubt that many professionals would consider me a serious threat as a designer. As with many academics, my career has included research, writing, editing, and publication in newspapers, theatre magazines, and disciplinary journals. Of course, I observe, evaluate, and critique. Above all, I teach.

After much consideration I discovered the common denominator in all of my work:

Rehearsal. Such an assertion offers a reminder to seek the profound and to search within oneself for the tools to find it. We should take public presentations very seriously. As the Judith Malina quotation suggests, the proper approach calls for immense responsibility balanced with continuous preparation. Even a casual student of communication realizes that speeches have changed lives, governments, and the course of history. Yet, something as seemingly simple as evoking laughter or tears means that something profound has occurred: one person has touched another. In countless instances I have seen people affected by a performance. Patrons have entered a theatre with dour expressions and exited with broad, beaming smiles. Audiences have sobbed unabashedly only to leap to their feet to thank the company for the privilege. At a small musical piece I attended, the gentleman across the aisle from me began weeping during the overture; during the remainder of the performance he offered gasps, shouts, and full-throated cries in one of the most intense examples of catharsis I have ever witnessed. I even found myself crying at my own directorial work when a woman seated near me in the back of the house whimpered in a way that reminded me of aspects of the material that had moved me in the first place.

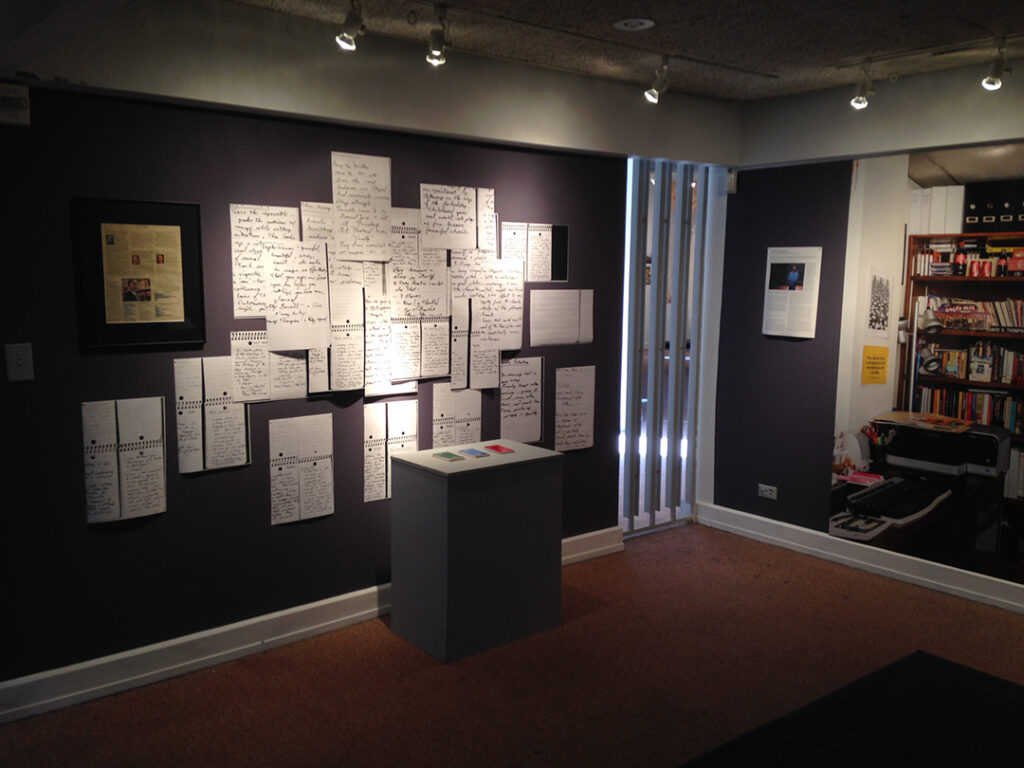

For these reasons and many more I find that I rehearse a great deal. One of the great misconceptions about the rehearsal process rests with the belief that it is simply repetition. While a rehearsal may include repetition, its deeper function involves revisiting material, whether that material exists in a script, score, or other form, or emerges through development. Each visit brings fresh awareness. Any of life’s circumstances—from mundane considerations of the weather to great personal calamity—can create a change in our perspective and, by extension, our understanding. Each discovery influences future choices; each choice leads to different realizations. And on it goes. Although the uses of the rehearsal process may seem varied and disparate on the surface, the application of the concepts finds similarities on a deeper level.

Organization is an important part of creation. It is important to develop structures or systems to assist accomplishment. For example, imposing a schedule ensures that each new visit to the project carries discipline, a sense of import which allows ideas to emerge. Having a set rehearsal time creates a space for dedicated consideration. It also encourages concentration as the dedication allows participants to leave their concerns at the door. In my case I can almost feel the checklist developing as I approach a project:

Get organized.

Create structure.

Break everything into acts, scenes, lines, or beats (for writing projects divide into chapters, paragraphs, sentences, words).

Make to-do lists.

Celebrate accomplishment.

Some people, possibly most people work better with a looming deadline. Theatre is that rare business that must deliver its product on time and for the price quoted. Opening night will always arrive—ready or not.

Writing is rewriting. Theatre artists call it rehearsal.

Directing is a lovely form of artistic expression because it is the antithesis of many forms of writing. Rather than a solitary endeavor other people are typically involved and the synergy of creation is shared. One of the great aspects of directing is that my collaborators are also my medium. Since they are living, breathing contributors they can adapt and change (a.k.a. they can easily correct my mistakes). As the performance develops, the product may or may not exactly resemble the original concept. In my case, the range of ideas is the most important. As long as my collaborators find a point within a range I have envisioned, other choices in other parts of the performance will mesh nicely. Rather than insisting on replicating an image precisely, the mutual development of an experience on the stage is far more satisfying.

Each rehearsal provides new information. Each encounter with the material yields something, no matter how small. Thus, all time spent on the process may contribute. Simultaneously, wasting someone else’s time should be avoided. In a collegiate theatre production, the rule of thumb holds that for each minute of performance the company anticipates, it should schedule an hour of rehearsal. A two-hour (120-minute) performance would require 120 hours of rehearsal. That is a part-time job for ten weeks, half-time employment for six weeks, or five continuous days spent with the same people. That requires commitment. One reward involves sitting in the theatre balcony watching a performance. Such a moment represents both a return to, and an extension of, the rehearsal process. The obvious difference is that the version on display for an audience has a richness of detail serving to place the flesh upon a structure that began as of skeleton of ideas.

I tend to rehearse nearly every public presentation that I make. At a minimum, I will review notes mentally and deliver key points aloud. This applies to class discussions and faculty meetings alike. After working as a marshal for commencement exercises for a decade, I still run through each briefing in full before I address the graduates. Preparing to read the names of those receiving degrees involves an hour of rehearsal nightly for the two weeks prior to the ceremony. Doing so offers a familiarity and comfort that minor distractions and inevitable changes in plan cannot disturb.

Voiceover acting in the studio is a distillation of the rehearsal process. Typically, a director or producer will have a specific vocal style or emotion in mind. The voice actor’s job is to provide that image. However, the work takes an additional step. Actors bring their own background and their own creative sense to each project. For small projects it is not unusual to offer multiple takes in different vocal styles, emotions, and even dialects. Instead of behaviors developed over days or weeks of rehearsal, instincts developed from previous projects, not to mention life experiences, inform choices for successive takes.

I suppose that if I am honest with myself, all of this was inevitable. I recall that as a child I was enamored by television of the age, particularly shows that were, or seemed, largely unscripted, live, or improvisational. Although my bedtime was far too early to enjoy The Tonight Show starring Johnny Carson, daytime programming once resembled the landscape now occupied by late night titans. Sure, I enjoyed scripted works, but I was also drawn to variety shows, talk shows, and game shows, events where the performance was not entirely hidden by character or situation. I found such images quite appealing. It took me many years to realize that what seemed like an innate talent to entertain on the spot actually derived from years of trial and error. Although audiences never saw it, I finally discovered that many performers had spent a lifetime rehearsing for spontaneous moments. I also found that pulling the swings of backyard swing set across the two side pieces created the image of an opening in a stage curtain. I have been rehearsing ever since.