showing/thinking: Nicole Stamant

Nicole Stamant is an associate professor and chair of English at Agnes Scott College. She holds a B.A. from Sweet Briar College and an M.A. and Ph.D. from Texas A&M University. Her teaching and scholarly interests include American studies, life writing studies, ethnic American literature, gender and sexual minority/queer studies, critical theory, disability studies, hospitality studies, and graphic narrative. Below are Professor Stamant’s reflections on her scholarly thinking and process, from the 2017 Dalton Gallery exhibition showing|thinking, a series of exhibitions that highlighted the work of faculty and staff on campus:

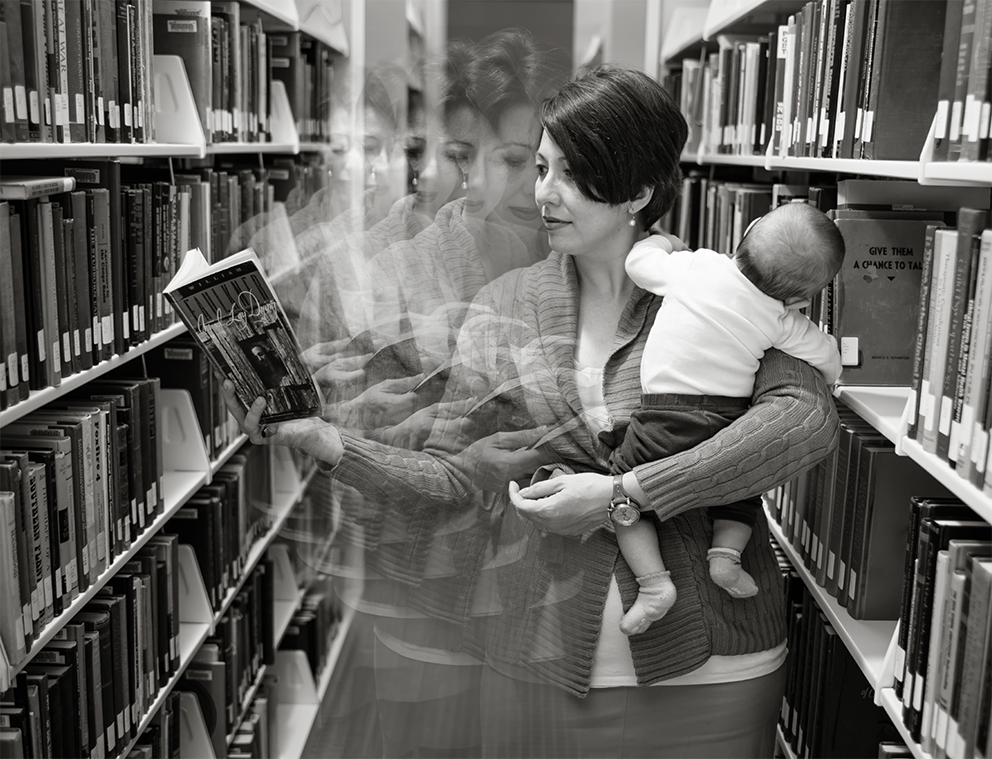

In my scholarship, I write about how other people write about their lives— how other people make sense of their worlds, their chaos, their histories, their families. I think about palimpsest and pentimento, geography and genre, memory and memorial. How we say what we say matters. As I write this, I am 9 months pregnant and I have an almost three- year-old. It turns out, unsurprisingly, that all of the writing routines and tricks on which I relied—that sustained me through graduate school, in my first few years as an English professor, and as I wrote my first book—don’t work for me anymore. One thing that we know about processes is that they should be dynamic: they are fluid systems that can and should shift to fit a reality that is likewise fluid and subject to change.

When I talk with student writers, they tell me that they get concerned if they find themselves starting somewhere other than at the beginning of a project, if they find themselves writing about something they hadn’t anticipated, if they find themselves changing their minds as they write. I encourage them to start in the middle—or wherever makes the most sense for them as they’re writing. I remind them that the inherent possibilities of writing are to end up somewhere new and potentially surprising. I support them in the writing that makes them vulnerable—to the world and to new ideas.

Right now, my own writing focuses on memoirs about families not unlike mine: mixed-race, in-between, liminal. As I was thinking about the best way to get into the writing of these stories, I realized that I would have to include my own story—the stories of my family, the stories that help provide the foundation for how I engage with the world. I don’t want to write about myself. I get no pleasure from the vulnerability of putting myself and my relationship to the world on the page. I prefer to write about how others write about their worlds; I prefer to read about how others create their worlds than narrativize my own. It doesn’t matter: the project demands that I am explicit about my own realities.

I thought I had a good handle on my family’s story: my mother is a light-skinned African American woman who grew up during the 1950s and 1960s in Pittsburgh, PA. My grandmother was also a light-skinned African American woman, descended from people enslaved in Jefferson County, Virginia (now West Virginia). My grandfather was born to a white mother—a Polish immigrant—and an African American father; it wasn’t until the early 2000s that he understood himself as biracial because the word was not widely in use before that. His ancestors were enslaved on the estate of President James Madison in Orange County, Virginia. My grandmother cleaned houses and, when she was able to quit that line of work, developed into an accomplished painter. My grandfather was a police officer. My mother is the middle child of five: she joined the Army after college and retired as a Colonel. She now works as an attorney for the VA and is an avid amateur genealogist.

Their stories are my stories, my siblings’ stories, and my children’s stories. And, stories are subject to change. A few months ago, my mother learned that, based on DNA, her father was likely not her biological father. My grandparents are deceased and my mother’s options for finding out the truth of her parentage are few. Did my grandmother have an affair? Women’s options in the mid-1950s were limited in terms of family planning. Was my grandmother assaulted? My mother recalls hearing about one of my grandmother’s employers’ roving hands; my uncle speculates that it was a colleague of my grandfather’s. How must she have felt while pregnant? Holding my mother, a newborn, up to the window for my grandfather to glimpse while he stood outside the hospital in Pittsburgh’s December snow? What does it mean for my mother? for my siblings? for me? Perhaps nothing; perhaps not nothing. There is no one to ask.

Regardless, our narratives have changed. We might be familiar with the truism that change is inevitable, but it’s also worth remembering that change is incessant. At times, it might feel sudden—with the birth of a child, a new job, a graduation—but it has been with us all along. We need to remember, though, that how we say what we say matters. The stories we know, our connections to them, and to one another, are central to making sense of our worlds, our lives, and our communities. Attending to those subtleties, and being willing to accept them and allow them into my life, has been my focus for these last several years.

When I write about others’ lives, I pay close attention to the sutures and seams exposed by the writer. There are some narratives that posit a unified subjectivity, a coherent self, a finished product. These narratives are not the ones that sit with me or inspire me. Instead, I gravitate toward those texts that are messy, the ones that reveal how fragmented we are and that remind readers about how we are always in-process, becoming. It is these texts, this writing, in which I find solace and optimism. Some might suggest that such a tangential relationship to ourselves is something to be feared or resisted; I posit that there is the possibility for play, for hope, and for expanding our conceptualization of ourselves, our words, and our worlds.

Photo credit TW Meyer