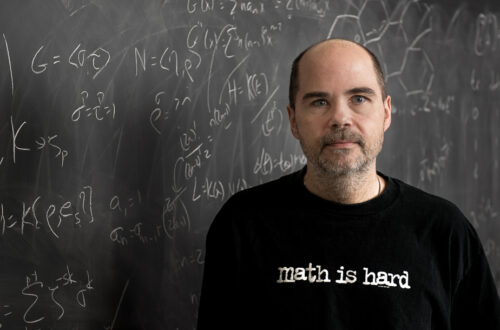

showing/thinking: Lock Rogers

Lock Rogers is an associate professor of biology at Agnes Scott College. He holds a B.S. from The University of Georgia and a Ph.D. from the University of Kentucky. Rogers’ area of research is evolutionary ecology focused on the effects of selection and environmental variance on the evolution of life histories. His teaching interests include ecology, behavioral ecology, and vertebrate evolution and anatomy. Below are Professor Rogers’ reflections on his scholarly thinking and process, from the 2015 Dalton Gallery exhibition showing|thinking, a series of exhibitions that highlighted the work of faculty and staff on campus:

“A scientist must be absolutely like a child. If he sees a thing, he must say that he sees it, whether it was what he thought he was going to see or not. See first, think later, then test. But always see first. Otherwise, you will only see what you were expecting.” -Douglas Adams

The house I grew up in was next to a creek. Actually, that’s not quite right; my Mom probably would have put it this way: The creek I grew up in was next to a house. I played in that creek so much that every shred of clothing I had was stained pink because the washing machine couldn’t quite get all the red clay out. One day, I was digging in the mud when I saw a little animal peering up at me. With all the good sense of a child, my hand flashed out and I grabbed it. It was a salamander, and it was the first of many of its kind to get picked up and looked at by me, kept for a day in my brother’s baby-bath, and eventually freed to tell its friends of its own adventure. Like any kid, I would check out books from the library to see if I could figure out what kinds of salamanders I had found. And, although I had no point of reference then, in retrospect, the diversity of that tiny creek was astounding.

A childhood of playing outside, salted with Saturday-morning episodes of Marine Boy, Sunday-night Jacques Cousteau specials, and Voyage to the Bottom of the Sea in my Dad’s lap when I could convince him to let me stay up, led me seamlessly to studying zoology at university. There, I worked as a lab and field assistant with professors and graduate students, and less than 24 hours after taking my last exam, I found myself at the West Indies Lab on the island of St. Croix, USVI. The project at WIL was a study of sexual selection in the species that I came to work on for my dissertation, and which I still work on today, the bluehead wrasse, Thalassoma bifasciatum. Our boat was very slow, and that left a lot of time for conversation as we made our way out to the reef each day. One day, the scientist leading the project, Bob Warner, and I were talking at the back of the boat, and he said something I did not understand. I asked him to explain, and I have never seen the world the same since.

We were talking about the evolution of the sex ratio. I had always thought that the reason about half of a species was male and the other half female would have had something to do with X and Y chromosomes. Bob explained that there was another factor at work as well. Imagine that the sex ratio was something far away from 1:1; for example, say for every female, there were 10 males. In that case, each female is very likely to reproduce, but, each male is not… in fact, the likelihood of a male reproducing successfully would be 1/10th that of a female. As a consequence, the gene causing an individual to develop as a female has ten times the fitness of the alternative gene resulting in a male. As a result of such selection, in the next generation, the female gene has become more common, and now the sex ratio is 9:1. Over time, the sex ratio continues to fall to 8:1, 5:1, 2:1, 1.1:1, etc. Eventually, the process slows to a stop when the sex ratio hits 1:1; at this point, there is no longer an advantage to the rarer sex because the rare sex is now as common as the common sex.

That experience has formed the basis for my work: reason and logic, underpinned by mathematics, leading to predictions about how the world ought to be, coupled with field experiments, mostly on fishes, testing those predictions.