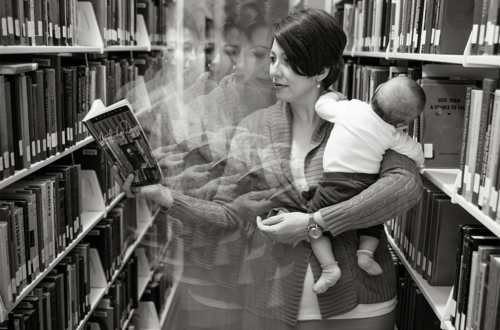

showing/thinking: Katherine Smith

Katherine Smith is a professor of art history at Agnes Scott College. She holds a B.A. from The University of Georgia and an M.A. and Ph.D. from New York University. Prof. Smith teaches courses in modern and contemporary art and architecture, including Modern Art, Modern Architecture, Contemporary Art and Theory, History of Photography, and Monuments. Her approach to teaching draws directly on the interdisciplinary nature of her research, which focuses on thinking across media. Her scholarship addresses intersections in American art and architecture from the 1960s to the present, with emphases on sculpture and urbanism. Her book The Accidental Possibilities of the City: Claes Oldenburg’s Urbanism in Postwar America has received support from The Graham Foundation for Advanced Studies in the Fine Arts. Below are Professor Smith’s reflections on her scholarly thinking and process, from the 2012 Dalton Gallery exhibition showing|thinking, a series of exhibitions that highlighted the work of faculty and staff on campus:

“All in all, the creative act is not performed by the artist alone; the spectator brings the work in contact with the external world by deciphering and interpreting its inner qualifications and thus adds his [or her] contribution to the creative act.” -Marcel Duchamp

I came across Duchamp’s “The Creative Act” by chance, which the artist, a founder of the Dada movement, would doubtless appreciate. Early in my graduate career, I was sitting in the library at the Museum of Modern Art researching Jasper Johns and considering ways of looking, experientially and theoretically, at his early paintings, which were called neo-Dada when first shown in the 1950s. This designation constituted an initial, critical attempt to create historical context for works that reintroduced recognizable images- flags and targets, numbers and letters- and entailed a dramatic departure from prevailing Abstract Expressionist styles. My interest was not in Johns’ neo-Dada label, but in the profound compositional dynamics that infuse his art from this period: his works not only mix abstraction and representation and cross boundaries between painting and sculpture, both radical gestures for that time, but they also, and for me most important, solicit an active participation from the viewer, who might embrace tasks like twisting keys, opening lids (as in Target with Plaster Casts), and reading newspapers partially hidden under layers of encaustic. Johns subtly and powerfully provokes an engagement that is optical and physical, multisensory and multidimensional, making the works incredibly innovative, even prescient.

Johns shares with Duchamp the understanding of the connection- integral and collaborative- between artist and viewer. As a teacher, I constantly shift between positions of creator and critic. As a scholar, I use words and images to craft and shape ideas. I came to the study of art history through my own studio practice, and it feels natural to me to be working with students and colleagues in both disciplines. I appreciate the ways that the members of our department work cooperatively within and between disciplines, experiencing and modeling the kind of dialogue that Duchamp describes and Johns dictates. The structure of our department- with an equal division between artists and historians- implicates an interdisciplinary that exists at the core of a liberal arts education, which we have embraced and cultivated in our courses. Our curriculum exemplifies liberal learning through rich combinations of practice and theory, technical facility and research methodology, process- and problem-based learning and critical inquiry, breadth and depth. We develop a community of scholars engaged in collaborative learning and independent thinking, respectful and constructive dialogue, and significant exploration of increasingly self-directed topics.

Collaboration guides my pedagogical practices and research methodologies. As I seek to explore intersections in art and architecture, my projects balance thorough visual analysis with historical and theoretical frameworks, often joining feminist theory with spatial politics and embracing issues of subjectivity and modes of perception. Many of my research topics have emerged directly from, and continue to be refined in, my teaching. As I have studied artistic and architectural partnerships and, within these projects, worked through ideas across disciplines and with my colleagues and my students, I have appreciated, analyzed, been challenged by and benefited from the profound dialogue Duchamp proposes.